Friday, May 22, 2009

Now I'm going to cover it up.

Now let's see where this lands.

Sunday, May 11, 2008

testing audio

Fr. Reginald Foster, "the Pope's own Latinist," teaches us how the Roman media would talk terrorism as he guides us through the terrors of Latin (terrores linguae Latinae)—

The archives of Fr. Foster's series "The Latin Lover" can be found here.

Friday, November 18, 2005

Cordesman: Foreign Fighters in Iraq

No one knows how many foreign volunteers are present in Iraq, or the current trend. US sources say on background that they believe that the Zarqawi movement may have roughly a thousand, and believe the number has increased since the January 30, 2005 election. At the same time, they note that a significant portion have been captured or killed, and feel such cadres are less sophisticated and well trained.

Reuvan Paz, a respected Israeli analyst has attempted to calculate the composition of foreign volunteers in Jihaddi-Salafi insurgent groups by examining the national origin of 154 insurgents killed in the fighting after the battle of Fallujah and through March 2005. He estimated that 94 (61%) were Saudi, 16 (10.4%) were Syrian, 13% (8.4%) were Iraqi, 11 (7.1% were Kuwaiti, 4 came from Jordan, 3 from Lebanon, 2 from Libya, 2 from Algeria, 2 from Morocco, 2 from Yemen, 2 from Tunisia, 1 from Palestine, 1 from Dubai, and one from the Sudan. He estimated that 33 of the 154 were killed in suicide attacks: 23 Saudis, 5 Syrian, 2 Kuwaiti, 1 Libyan, 1 Iraqi, and 1 Moroccan. These figures are drawn from a very small sample, and are highly uncertain, but they do illustrate the diversity of backgrounds.1

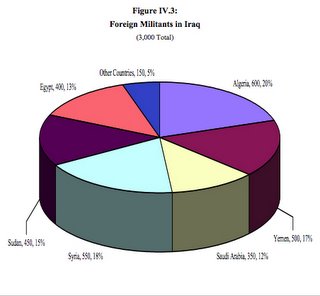

The Saudi National Security Assessment Project, and Nawaf Obaid, have made a more detailed estimate, and conclude there are approximately 3,000 foreign fighters in Iraq (See Figure IV.3). This figure, and the breakdown by nationality, are rounded “best estimates,” based on reports of Saudi and other intelligence services; specifically, on the interrogations of hundreds of captured militants and a comprehensive analysis of militant activities. This includes interviews and analysis of activities by both Saudi and non-Saudi militants. Also consulted were intelligence reports prepared by other regional governments, which provided not only names of militants, but also valuable information on the networks that they relied upon to enter Iraq and conduct their activities.

The conclusion of the Saudi investigation was that the number of Saudi volunteers in August 2005 was around 12% of the foreign contingent (approximately 350), or 1.2% of the total insurgency of approximately 30,000. Algerians constitute the largest contingent at 20%, followed closely by Syrians (18%), Yemenis (17%), Sudanese (15%), Egyptians (13%) and those from other states (5%). Discussions with US and Iraqi experts indicated that they felt that Saudi estimates were roughly correct, although they cautioned that they did not have reliable numbers for either the total number of volunteers or their origin by country.

If there are anything like 3,000 foreign fighters in Iraq, this poses a serious threat. In any case, the exact numbers are largely irrelevant. All it takes is enough volunteers to continue to support suicide attacks and violent bombings, and to seek to drive Iraqi Sunnis towards a major and intense civil war. Such volunteers also pose a threat because their actions gave Bin Laden and other neo-Salafi extremist movements publicity and credibility among the angry and alienated in the Islamic world, and because many were likely to survive and be the source of violence and extremism in other countries.

Nevertheless, these numbers pale beside those for the Iraqis themselves. By all reports, the insurgency remains largely homegrown. US experts and top level Iraqi officials estimated in November 2005 that at least 90% of the fighters were Iraqi and the total might be closer to 94% to 96%.. Coalition sources also indicated that only 3.8% of some 13,300 detainees held in the fall of 2005 were foreign, and this percentage was lower than it had been in the early winter of 2005. Major General Rick Lynch in the Coalition command in Baghdad stated in October that only 376 of the detainees taken in 2005 were foreign: 78 Egyptians, 66 Syrians, 41 Sudanese, 32 Saudis, 1 American, and 1 Briton. These numbers had not changed significantly as of November 1, although the total number of detainees had risen to 13,900. (Out of this total, 5,569 had already been held for six months, 3,801 for a year, and 229 for two years. The total include some 752 at Fort Suse in northeast Iraq, 113 at Camp Cropper and $,788 at Abu Ghraib in Baghdad, and 6,780 at Camp Bucca in Southeastern Iraq. There were an additional 1,136 detainees in various brigade and internment facilities as of November 9, 2005.)2

These figures mark a sharp contrast to some allegations that the insurgency was being driven by large numbers of foreign volunteers, and that a flood of new volunteers came in 2005. As Major General Joseph J. Taluto, the commander of the US Army’s 42nd Infantry Division, which was based in Tikrit put it, “The foreign fighters attacks tend to be more spectacular, but the local national, the Saddamists, the Iraqi rejectionists, are much more problematic.3

Saudi Militants in Iraq: A Case Study

The Coalition and Iraqi government have not released any significant details on their estimates of the number of foreign volunteers, their origin, or their motives. The Saudi intelligence services have, however, made a major effort to estimate the number of Saudi infiltrators that move across the Saudi border – or far more often transit through third states like Syria.

As of August 2005, approximately 352 Saudis were thought to have successful entered Iraq (and an additional 63 had been stopped at the border by Saudi security services). Of these, 150 were thought to be active, 72 were known from al-Qa'ida compiled lists to be active in Iraq,4 74 were presumed in detention (a maximum of 20 in US custody and 3 in Kurdish), and 56 were presumed dead (See Figure IV.4).

Interrogations and other Saudi intelligence gathering operations revealed that these individuals did not come exclusively from a single geographical region in Saudi Arabia, but from various areas in the Kingdom, especially from the South, Hijaz, and Najd. They were usually affiliated with the most prominent conservative tribes and were generally middle class. Most are employed, many are educated, and all were Sunni.5 (For more background, see “Case Studies” in Appendix I.)

[Figure]

As part of a massive crackdown on Saudi militants attempting to enter Iraq, the Saudi government has interrogated dozens of nationals either returning from Iraq or caught at the border. The average age of these fighters was 17-25, but a few were older. Some had families and young children. In contrast, other fighters from across the Middle East and North Africa tended to be in their late 20s or 30s.

The Saudi infiltrators were also questioned by the intelligence services about their motives for joining the insurgency. One important point was the number who insisted that they were not militants before the Iraq war. Of those who were interrogated, a full 85% were not on any government watch list (which comprised most of the recognized extremists and militants), nor were they known members of al-Qa'ida.

The names of those who died fighting in Iraq generally appear on militant websites as martyrs, and Saudi investigators also approached the families of these individuals for information regarding the background and motivation of the ones who died. According to these interviews as well, the bulk of the Saudi fighters in Iraq were driven to extremism by the war itself.

Most of the Saudi militants in Iraq were motivated by revulsion at the idea of an Arab land being occupied by a non-Arab country. These feelings were intensified by the images of the occupation they see on television and the Internet – many of which come from sources intensely hostile to the US and war in Iraq, and which repeat or manipulate “worst case” images.

The catalyst most often cited was Abu Ghraib, though images from Guantanamo Bay were mentioned. Some recognized the name of a relative or friend posted on a website and feel compelled to join the cause. These factors, combined with the agitation regularly provided by militant clerics in Friday prayers, helped lead them to volunteer.

In one case, a 24-year-old student from a prominent Saudi tribe -- who had no previous affiliation with militants -- explained that he was motivated after the US invasion, to join the militants by stories he saw in the press, and through the forceful rhetoric of a midlevel cleric sympathetic to al-Qa'ida. The cleric introduced him and three others to a Yemeni, who unbeknownst to them was an al-Qa'ida member.

After undergoing several weeks of indoctrination, the group made its way to Syria, and then was escorted across the border to Iraq where they met their Iraqi handlers. There they assigned to a battalion, comprised mostly of Saudis (though those planning the attacks were exclusively Iraqi). After being appointed to carry out a suicide attack, the young man had second thoughts and instead, returned home to Saudi Arabia where he was arrested in January 2004. The cleric who had instigated the whole affair was also brought up on terrorism charges and is expected to face a long jail term. The Yemeni alQa'ida member was killed in December 2004 following a failed attack on the Ministry of Interior.

There are other similar stories regarding young men who were enticed by rogue clerics into taking up arms in Iraq. Many were instructed to engage in suicide attacks and as a result, never return home. Interrogations of nearly 150 Saudis suspected of planning to the join the Iraqi insurgency indicate that they were heeding the calls of clerics and activists to “drive the infidels out of Arab land.”

Like Jordan and most Arab countries, the Saudi government has sought to limit such calls for action, which inevitably feed neo-Salafi extremist as the expense of legitimate interpretations of Islam. King Abdullah has issued a strong new directive that holds those who conceal knowledge of terrorist activities as guilty as the terrorists themselves. However, many religious leaders and figures in Arab nations have issued fatwas stating that waging jihad in Iraq is justified by the Koran due to its “defensive” nature. To illustrate, in October 2004, several clerics in Saudi Arabia said that, “it was the duty of every Muslim to go and fight in Iraq.”6

On June 20, 2005, the Saudi government released a new list of 36 known al-Qa’ida operatives in the Kingdom (all but one of those released on previous lists had been killed by Saudi security forces, so these individuals represented the foot soldiers of al-Qa’ida, and they were considered far less dangerous). After a major crackdown in the Kingdom, as many as 21 of these low-level al-Qa’ida members fled to Iraq.

Interior Minister Prince Nayef commented that when they return, they could be even “tougher” than those who fought in Afghanistan. “We expect the worse from those who went to Iraq,” he said. “They will be worse and we will be ready for them.” According to Prince Turki al-Faisal, the former Saudi Intelligence Chief and the new Ambassador to the US, approximately 150 Saudis are currently operating in Iraq.7

Unlike the foreign fighters from poor countries such as Yemen and Egypt, Saudis entering Iraq often brought in money to support the cause, arriving with personal funds between $10,000-$15,000. Saudis are the most sought after militants; not only because of their cash contributions, but also because of the media attention their deaths as “martyrs” bring to the cause. This is a powerful recruiting tool. Because of the wealth of Saudi Arabia, and its well-developed press, there also tends to be much more coverage of Saudi deaths in Iraq than of those from poorer countries.

In contrast, if an Algerian or Egyptian militant dies in Iraq, it is unlikely that anyone in his home country will ever know. For instance, interrogations revealed that when an Algerian conducts a suicide bombing, the insurgency rarely has a means of contacting their next of kin. Saudis, however, always provide a contact number and a welldeveloped system is in place for recording and disseminating any “martyrdom operations” by Saudis.

Syria and Foreign Volunteers

The Saudi government had some success in its efforts to seal the border between the Kingdom and Iraq. However, several other countries provided relatively easy passage to Saudi and other foreign volunteers, and have repeatedly been accused by Iraqi authorities of not doing enough to prevent foreign fighters from entering Iraq.

Iraqi, Jordanian, and Saudi officials have all identified Syria as the biggest problem, but preventing militants from crossing its 380-mile border with Iraq is daunting. According to The Minister of Tourism, Syria was fast becoming one of the largest tourist destinations in the Middle East. In 2004, roughly 3.1 million tourists visited the country; the number of Saudis arriving in just the first seven months of 2005 increased to 270,000 from 230,000 in the same period in 2004.8 Separating the legitimate visitors from the militants is nearly impossible, and Saudi militants have taken advantage of this fact (See Appendix 1: Case Studies).

Most militants entering Iraq from Syria do so at a point just south of the mountainous Kurdish areas of the north, which is sparsely inhabited by nomadic Sunni Arab tribes, or due east from Dair al-Zawr into Iraq’s Anbar province. Crossing near the southern portion of the border, which is mainly desert and is heavily occupied by Syrian and U.S. forces, is seldom done. The crossing from Dair Al-Zawr province was the preferred route through the summer of 2005, because the majority of the inhabitants on both sides of the border were sympathetic to the insurgency, the scattering of villages along the border provides ample opportunity for covert movement, and constant insurgent attacks in the area are thought to keep the U.S. forces otherwise occupied. According to intelligence estimates, the key transit point here – for both Saudis and other Arabs – is the Bab al-Waleed crossing.

Even if Syria had the political will to completely and forcefully seal its border, it lacked sufficient resources to do so (Saudi Arabia has spent over $1.2 billion in the past two years alone to secure its border). As a result, it relies heavily upon screening those who enter the country. A problem with this method, however, is the difficulty of establishing proof of residency in Syria as well as the difficulties with verifying hotel reservations. Moreover, there is no visa requirement for Saudis to enter the country. Syria does, however, maintain a database of suspected militants, and several dozen Saudis have been arrested at the border. However, pressuring the Syrians additionally to tighten security could be both unrealistic and politically sensitive.

An April 2003 report by Italian investigators described Syria as a “hub” for the relocation of Zarqawi's group to Iraq. According to the report, “transcripts of wiretapped conversations among the arrested suspects and others paint a detailed picture of overseers in Syria coordinating the movement of recruits and money between Europe and Iraq.”9

At the same time, there are those who claim the Syrian authorities are being too forceful in their crackdown of Saudis in the country. There have been recent reports that Syria has engaged in the systematic abuse, beating and robbery of Saudi tourists, a charge that Syria denies. According to semi-official reports published in al-Watan, released prisoners alleged that Syrian authorities arbitrarily arrested Saudis on the grounds that they were attempting to infiltrate Iraq to carry out terrorist attacks.

The former detainees maintained that they were “targeted for arrest in Syria without any charges.” They went on to say that, “if they had intended to sneak into Iraq, Saudi authorities would have kept them in custody when they were handed over to that country.” According to the Syrian Minister of Tourism, Saadallah Agha Kalaa, “no Saudi tourists have been harassed in Syria or subjected to unusual spate of robberies. Those who are spreading these rumors are seeking to harm Syria, which is a safe tourist destination.” In the murky world of the Syrian security services, it is difficult to discern the truth. Suffice it to say that the problem of successfully halting the traffic of Saudis through Syria into Iraq is overwhelmingly difficult, politically charged, and operationally challenging.

Iran and Foreign Volunteers

Iraq also shares a long and relatively unguarded border with Iran, however, as a non-Sunni non-Arab country. Few Saudi and other Sunni extremists seem to use it as a point of entry. Saudi authorities have, however, captured a handful of militants who have gone through Iran and four were apprehended after passing from Iran to the United Arab Emirates.

Iran is also a major source of funding and logistics for militant Shiite groups in Iraq (mainly SCIRI). According to regional intelligence reports, Iran is suspected of arming and training some 40,000 Iraqi fighters with a view towards fomenting an Islamic revolution in Iraq. Most of these Iraqi Shiites are former prisoners of war captured during the Iran-Iraq war.10

1Reven [sic] Paz, “Arab Volunteers Killed in Iraq: An Analysis,” PRISM Series of Global Jihad, Volume 3 (2005), Number 1/3, March 2005. (www.e-prism.org) [back]

2Jonathan Finer, “Among Insurgents in Iraq, Few Foreigners Are Found,” Washington Post, November 17, 2005, p. A-1; Katherine Shraeder, “83,000 Foreigners Have Been Detained in War on Terror,” Associated Press, November 17, 2005, 06:10. [back]

3[Footnote 3 had no text in the PDF document. This quote was also given in the article by Jonathan Finer in the Washington Post "Among Insurgents in Iraq, Few Foreigners Are Found."

4The Paz study places the number of Saudis in Iraq much higher, at 94. However, this study based much of its evidence on an analysis of an al-Qa’ida compiled “martyr website.” Further investigation revealed that this list was unreliable and the numbers were most likely inflated for propaganda and recruiting purposes (one Saudi captured in November 2004 involved in compiling these lists admitted as much). For instance, further investigations revealed that 22% of the Saudis listed as martyrs on this site were actually alive and well in the Kingdom. Furthermore, an additional investigation has disclosed that many others who claimed that they would be going to Iraq were merely boasting on Internet sites – they too were found to be living in the Kingdom. Finally, since the “list” was compiled by Saudis, it is highly likely that they would over-represent their countrymen, as they had the most contact with and knowledge of fellow Saudis. [back]

5Source: Saudi National Security Assessment Project. [back]

6“Study cites seeds of terror in Iraq: War radicalized most, probes find,” Bryan Bender, The Boston Globe, July 17, 2005. [back]

7“Saudi Arabia says Ready to Beat Militants from Iraq,” Dominic Evans, (Reuters, July 10, 2005). [back]

8The Ministry has also issued numbers totaling some 6.2 million for the same year, “Syria Sets Sights on Tourism to Revitalize Economy,” Nawal Idelbi, Daily Star, June 30, 2005; In 2005, the Ministry announced that tourism had reached 1.41 million in the first half of 2005, “Tourism in Syria Sees Major Increase,” www.syrialive.net, July 16, 2005. [back]

9"Probe Links Syria, Terror Network," The Los Angeles Times, 16 April 2004. Sebastian Rotella, “A Road to Ansar Began in Italy: Wiretaps are Said to Show how al Qa’ida Sought to Create in Northern Iraq a Substitute for Training Camps in Afghanistan," The Los Angeles Times, 28 April 2003. [back]

10The role of Iran in post-Saddam Iraq goes beyond the pale of this study, but it is important to note that intelligence assessments clearly show Iran is by far the most dangerous destabilizing factor in Iraq today. The Iranian-backed Shitte forces are by far the most organized and positioned to influence future events. [back]